Days in the Woods

|

|

Adventure-based education (aka “experiential learning”) can be helpful in creating high performing teams. However, going out in the woods, doing “trust falls”, or rappelling down a cliff does not result automatically in world-class teams. From years of personal experience with adventure-based learning, I have found that these elements are essential:

1, Willing participants. Just because your boss says you must is not enough of a reason to be enthused about a treetop “high ropes” course or any other adventure program. All of my adventure learning activities, personal and organizational, were voluntary. Of course, being there does not suggest an uncritical acceptance nor that your experience will be superior to a traditional indoor class - it is very much up to the open and willing individual learner to take what he or she learns and make the transfer from the woods to the workplace.

Reminiscing over a group photo from my former employer’s first adventure event - an overnight rock climb at Hanging Rock State Park - I see several faces of people who were instrumental in leading our successful change initiative. They were open and willing to look at how we worked and how we could do better. I like to think that what happened at Hanging Rock influenced us in positive ways; maybe it was only to confirm how we were going to work together, but I think we did see each other differently – in good ways - after that weekend at Hanging Rock.

Caption: Established new relationships in this wildly fun activity, everyone getting up on a two-foot square platform. Try doing this while maintaining the hierarchy!

2. Tuned-in facilitators (the people leading the event.) These leaders have to focus discussion so it addresses the reasons for being there – backpacking or the rock climb or the “low ropes” is not the real reason. Mastering the two person “Wild Woozy” – something I have never done – is an accomplishment, but it is not the end reason for the activity.

How you and your partner worked together is the learning. In my rock climb example, the real reason was to give permission to try out new ways, to support each other, to take risks and to realize there were multiple ways of doing something. And, it was important for peers and supervisors to see each other in ways different from an office setting.

3. Peers as participants. The people with whom you work need to be present. In my case, while the adventures were offered to the organization at large, most of the participants were my co-workers and divisional supervisors. On a rare occasion, we would have a participant from an external group; that was good, but I realized the limitations of one person’s being able to do much of anything – beyond personal growth - with what she learned from our day(s) in the woods.

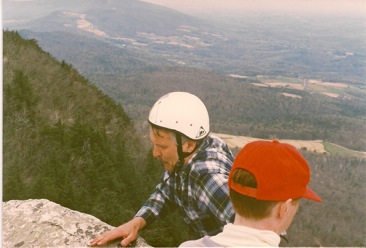

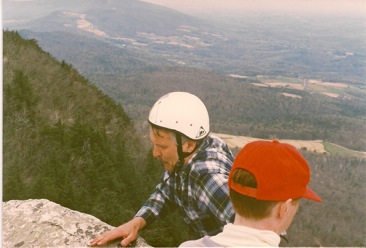

4. The leader as participant. This is risky. The boss might slip and fall into a bog hole and be left wet and feeling like a doofus. Or the leader might struggle up the cliff acrophobically, for all to see.

Caption: I had a hard time making it to the top.

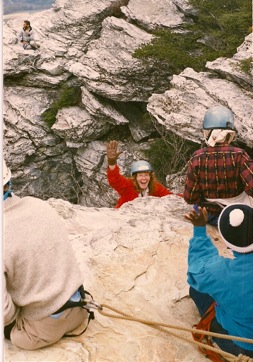

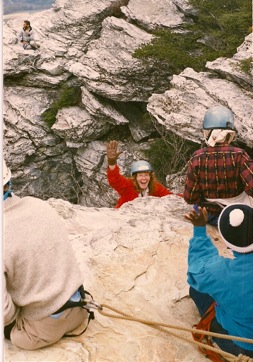

A junior staff member turned out to be a prodigious rock climber and did the climb twice; stopping both times to relish the open landscape view 2500 feet below. Here’s another picture of one joyful participant reaching the top. I wish I’d felt that way!

Or, the boss’s idea for solving a problem might be ignored by the group. You, the boss, have to be ready for that to happen. When group members see the leader supporting an idea, regardless of source, they understand the boss appreciates good ideas from all over, not just from the titled. Once the staff see you more as a colleague and less a supervisor, the more likely they will become active participants in your change initiative.

5. A real challenge. There has to be a manageable and meaningful challenge for every participant. You may relish dangling from a rope against the cold granite of a cliff face; but you might not be the happiest camper when waking up in a wet sleeping bag, in a drenching rain and figuring out, with the group, how to start a fire, keep dry and get hot food.

And challenges do not always require a win. Whether a participant makes it to the top or not is less important than for the difficulty encountered and dealt with along the way. Adventure learning adds challenge through perceived risk.

Caption: The safety drill before rappelling into the Hurricane Island quarry.

In the rock climb, we’re harnessed in, wearing helmets, with belayers at the top and bottom of the climb; injuries - beyond scrapes and bruises - are highly unlikely. Most of us will be challenged – to the point of trembling legs - and if we make it, we’ll be exhilarated (I did it!) and happy it’s over. We may be surprised at our meeting the challenge head on; even better if we thought we could not!

What made the difference? It’s something to think about the next time we find ourselves up against it at work.

And, if we do not make it up the cliff – “failure” - we’ll also have something to think about. What got in the way? What would I do differently? Did I use all available resources?

Caption: Setting forth into the unknown. An open water crossing, Penobscot Bay, Maine Coast.

6. Team-based adventure. Being there has to be more about the team, the group than the individual. That is why the “Wall” activity, which cannot be performed solo, is a better team builder than is the infamous Pamper Pole.

While I learned a great deal about myself from my Outward Bound expeditions (with strangers) I also learned about how groups evolve and about leadership and followership and about how a group may fail to develop. I learned how unusual it is for a group to “click”, to feel good about itself and not worry about who’s top dog or if everyone is doing his or her fair share of cooking or rowing or cleaning up.

7. A continuum of learning. Finally, your adventure has to be part of a staff development program that builds on and reinforces what is learned with each adventure. Our organizational approach to staff development was, alack, more hit and miss, with few offerings – we did not have a training platform on which to build. Follow up seminars could have introduced theories and discussion about group dynamics, conflict resolutions, team development, and communication. Another time.

For more on this topic, see Leading from the Middle’s Chapter 19: “A Gift from the Woods” and Chapter 4: “Letting Go: A Reflection on Teams That Were.”

1, Willing participants. Just because your boss says you must is not enough of a reason to be enthused about a treetop “high ropes” course or any other adventure program. All of my adventure learning activities, personal and organizational, were voluntary. Of course, being there does not suggest an uncritical acceptance nor that your experience will be superior to a traditional indoor class - it is very much up to the open and willing individual learner to take what he or she learns and make the transfer from the woods to the workplace.

Reminiscing over a group photo from my former employer’s first adventure event - an overnight rock climb at Hanging Rock State Park - I see several faces of people who were instrumental in leading our successful change initiative. They were open and willing to look at how we worked and how we could do better. I like to think that what happened at Hanging Rock influenced us in positive ways; maybe it was only to confirm how we were going to work together, but I think we did see each other differently – in good ways - after that weekend at Hanging Rock.

Caption: Established new relationships in this wildly fun activity, everyone getting up on a two-foot square platform. Try doing this while maintaining the hierarchy!

2. Tuned-in facilitators (the people leading the event.) These leaders have to focus discussion so it addresses the reasons for being there – backpacking or the rock climb or the “low ropes” is not the real reason. Mastering the two person “Wild Woozy” – something I have never done – is an accomplishment, but it is not the end reason for the activity.

How you and your partner worked together is the learning. In my rock climb example, the real reason was to give permission to try out new ways, to support each other, to take risks and to realize there were multiple ways of doing something. And, it was important for peers and supervisors to see each other in ways different from an office setting.

3. Peers as participants. The people with whom you work need to be present. In my case, while the adventures were offered to the organization at large, most of the participants were my co-workers and divisional supervisors. On a rare occasion, we would have a participant from an external group; that was good, but I realized the limitations of one person’s being able to do much of anything – beyond personal growth - with what she learned from our day(s) in the woods.

4. The leader as participant. This is risky. The boss might slip and fall into a bog hole and be left wet and feeling like a doofus. Or the leader might struggle up the cliff acrophobically, for all to see.

Caption: I had a hard time making it to the top.

A junior staff member turned out to be a prodigious rock climber and did the climb twice; stopping both times to relish the open landscape view 2500 feet below. Here’s another picture of one joyful participant reaching the top. I wish I’d felt that way!

Or, the boss’s idea for solving a problem might be ignored by the group. You, the boss, have to be ready for that to happen. When group members see the leader supporting an idea, regardless of source, they understand the boss appreciates good ideas from all over, not just from the titled. Once the staff see you more as a colleague and less a supervisor, the more likely they will become active participants in your change initiative.

5. A real challenge. There has to be a manageable and meaningful challenge for every participant. You may relish dangling from a rope against the cold granite of a cliff face; but you might not be the happiest camper when waking up in a wet sleeping bag, in a drenching rain and figuring out, with the group, how to start a fire, keep dry and get hot food.

And challenges do not always require a win. Whether a participant makes it to the top or not is less important than for the difficulty encountered and dealt with along the way. Adventure learning adds challenge through perceived risk.

Caption: The safety drill before rappelling into the Hurricane Island quarry.

In the rock climb, we’re harnessed in, wearing helmets, with belayers at the top and bottom of the climb; injuries - beyond scrapes and bruises - are highly unlikely. Most of us will be challenged – to the point of trembling legs - and if we make it, we’ll be exhilarated (I did it!) and happy it’s over. We may be surprised at our meeting the challenge head on; even better if we thought we could not!

What made the difference? It’s something to think about the next time we find ourselves up against it at work.

And, if we do not make it up the cliff – “failure” - we’ll also have something to think about. What got in the way? What would I do differently? Did I use all available resources?

Caption: Setting forth into the unknown. An open water crossing, Penobscot Bay, Maine Coast.

6. Team-based adventure. Being there has to be more about the team, the group than the individual. That is why the “Wall” activity, which cannot be performed solo, is a better team builder than is the infamous Pamper Pole.

While I learned a great deal about myself from my Outward Bound expeditions (with strangers) I also learned about how groups evolve and about leadership and followership and about how a group may fail to develop. I learned how unusual it is for a group to “click”, to feel good about itself and not worry about who’s top dog or if everyone is doing his or her fair share of cooking or rowing or cleaning up.

7. A continuum of learning. Finally, your adventure has to be part of a staff development program that builds on and reinforces what is learned with each adventure. Our organizational approach to staff development was, alack, more hit and miss, with few offerings – we did not have a training platform on which to build. Follow up seminars could have introduced theories and discussion about group dynamics, conflict resolutions, team development, and communication. Another time.

For more on this topic, see Leading from the Middle’s Chapter 19: “A Gift from the Woods” and Chapter 4: “Letting Go: A Reflection on Teams That Were.”

John Lubans - portrait by WSJ

John Lubans - portrait by WSJ